The peritoneum /ˌpɛrɨtənˈiəm/ is the serous membrane that forms the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal (or coelomic) organs, and is composed of a layer of mesothelium supported by a thin layer of connective tissue. The peritoneum supports the abdominal organs and serves as a conduit for their blood vessels, lymph vessels, and nerves.

The abdominal cavity (the space bounded by the vertebrae, abdominal muscles, diaphragm, and pelvic floor) should not be confused with the intraperitoneal space (located within the abdominal cavity, but wrapped in peritoneum). The structures within the intraperitoneal space are called "intraperitoneal" (e.g. the stomach), the structures in the abdominal cavity that are located behind the intraperitoneal space are called "retroperitoneal" (e.g. the kidneys), and those structures below the intraperitoneal space are called "subperitoneal" or "infraperitoneal" (e.g. the bladder).

Structure

Types

Although they ultimately form one continuous sheet, two types or layers of peritoneum and a potential space between them are referenced:

- The outer layer, called the parietal peritoneum, is attached to the abdominal wall and the pelvic walls.

- The inner layer, the visceral peritoneum, is wrapped around the internal organs that are located inside the intraperitoneal space. It is thinner than the parietal peritoneum.

- The potential space between these two layers is the peritoneal cavity; it is filled with a small amount (about 50 mL) of slippery serous fluid that allows the two layers to slide freely over each other.

- The term mesentery is often used to refer to a double layer of visceral peritoneum. There are often blood vessels, nerves, and other structures between these layers. The space between these two layers is technically outside of the peritoneal sac, and thus not in the peritoneal cavity.

Subdivisions

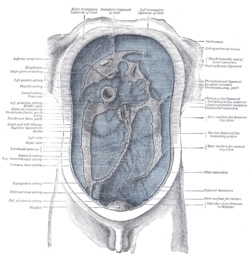

Peritoneal folds are omenta, mesenteries and ligaments; they connect organs to each other or to the abdominal wall. There are two main regions of the peritoneum, connected by the epiploic foramen (also known as the omental foramen or foramen of winslow):

- The greater sac (or general cavity of the abdomen), represented in red in the diagrams above.

- The lesser sac (or omental bursa), represented in blue. The lesser sac is divided into two "omenta":

- The lesser omentum (or gastrohepatic) is attached to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the liver.

- The greater omentum (or gastrocolic) hangs from the greater curve of the stomach and loops down in front of the intestines before curving back upwards to attach to the transverse colon. In effect it is draped in front of the intestines like an apron and may serve as an insulating or protective layer.

The mesentery is the part of the peritoneum through which most abdominal organs are attached to the abdominal wall and supplied with blood and lymph vessels and nerves.

Omenta

Mesenteries

Other ligaments and folds

In addition, in the pelvic cavity there are several structures that are usually named not for the peritoneum, but for the areas defined by the peritoneal folds:

Classification of abdominal structures

The structures in the abdomen are classified as intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal or infraperitoneal depending on whether they are covered with visceral peritoneum and whether they are attached by mesenteries (mensentery, mesocolon).

Structures that are intraperitoneal are generally mobile, while those that are retroperitoneal are relatively fixed in their location.

Some structures, such as the kidneys, are "primarily retroperitoneal", while others such as the majority of the duodenum, are "secondarily retroperitoneal", meaning that structure developed intraperitoneally but lost its mesentery and thus became retroperitoneal.

Development

The peritoneum develops ultimately from the mesoderm of the trilaminar embryo. As the mesoderm differentiates, one region known as the lateral plate mesoderm splits to form two layers separated by an intraembryonic coelom. These two layers develop later into the visceral and parietal layers found in all serous cavities, including the peritoneum.

As an embryo develops, the various abdominal organs grow into the abdominal cavity from structures in the abdominal wall. In this process they become enveloped in a layer of peritoneum. The growing organs "take their blood vessels with them" from the abdominal wall, and these blood vessels become covered by peritoneum, forming a mesentery.

Peritoneal folds develop from the ventral and dorsal mesentery of the embryo.

Clinical significance

Peritoneal dialysis

In one form of dialysis, called peritoneal dialysis, a glucose solution is sent through a tube into the peritoneal cavity. The fluid is left there for a prescribed amount of time to absorb waste products, and then removed through the tube. The reason for this effect is the high number of arteries and veins in the peritoneal cavity. Through the mechanism of diffusion, waste products are removed from the blood.

Peritonitis

Peritonitis refers to the inflammation of the peritoneum. It is more commonly associated to infection from a punctured organ of the abdominal cavity. It can also be provoked by the presence of fluids that produce chemical irritation, such as gastric acid or pancreatic juice. Peritonitis causes fever, tenderness, and pain in the abdominal area, which can be localized or diffuse. The treatment involves rehydration, administration of antibiotics, and surgical correction of the underlying cause. Mortality is higher in the elderly and if present for a prolonged time.

Primary peritoneal carcinoma

Primary peritoneal cancer is a cancer of the cells lining the peritoneum.

History

Etymology

Peritoneum is derived from Greek via Latin. Peri- means around, while -ton- refers to stretching. Thus, peritoneum means stretched around or stretched over.

Additional images

References

- Tortora, Gerard J., Anagnostakos, Reginald Merryweather, Nicholas P. (1984) Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, Harper & Row Publishers, New York ISBN 0-06-046656-1

External links

- Anatomy photo:37:03-0102 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Overview and diagrams at colostate.edu