An International Nonproprietary Name (INN) is an official generic and nonproprietary name given to a pharmaceutical drug or active ingredient. INNs make communication more precise by providing a unique standard name for each active ingredient, to avoid prescribing errors. The INN system has been coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 1953.

Having unambiguious standard names for each drug is important because a drug may be sold by many different brand names, or a branded medication may contain more than one drug. For example, the branded medications Celexa, Celapram and Citrol all contain the same active ingredient: citalopram; and the branded preparation Lemsip contains two active ingredients: paracetamol and phenylephrine.

Each drug's INN is unique but may contain a word stem that is shared with other drugs of the same class, for example the beta blocker drugs propranolol and atenolol share the -olol suffix, and the benzodiazepine drugs lorazepam and diazepam share the -azepam suffix.

The WHO issues INNs in English, Latin, French, Russian, Spanish, Arabic, and Chinese, and a drug's INNs are often cognate across most or all of the languages, with minor spelling or pronunciation differences, for example: "paracetamol" (en) "paracetamolum" (la), "paracétamol" (fr) and "парацетамол" (ru). An established INN is known as an rINN (recommended INN), while a name that is still being considered is called a pINN (proposed INN).

Name stems

Drugs from the same therapeutic or chemical class are usually given names with the same stem. Stems are mostly placed word-finally, but in some cases word-initial stems are used. They are collected in a publication informally known as the Stem Book.

Examples are:

- -anib for angiogenesis inhibitors (e.g. pazopanib)

- -anserin for serotonin receptor antagonists, especially 5-HT2 antagonists (e.g. ritanserin and mianserin)

- -arit for antiarthritic agents (e.g. lobenzarit)

- -ase for enzymes (e.g. asparaginase)

- -azepam for benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam and oxazepam)

- -caine for local anaesthetics (e.g. procaine or cocaine)

- -cain- for class I antiarrhythmics (e.g. procainamide)

- -coxib for COX-2 inhibitors, a type of anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. celecoxib)

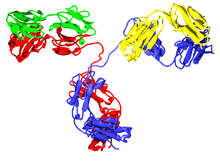

- -mab for monoclonal antibodies (e.g. infliximab); see Nomenclature of monoclonal antibodies

- -navir for antiretroviral protease inhibitors (e.g. darunavir)

- -olol for beta blockers (e.g. atenolol)

- -pril for ACE inhibitors (e.g. captopril)

- -sartan for angiotensin II receptor antagonists (e.g. losartan)

- -tinib for tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. imatinib)

- -vastatin for HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, a group of cholesterol lowering agents (e.g. simvastatin)

- -vir for antivirals (e.g. aciclovir or ritonavir)

- arte- for artemisinin antimalarials (e.g. artemether)

- cef- for cefalosporins (e.g. cefalexin)

- io- for iodine-containing radiopharmaceuticals (e.g. iobenguane)

Linguistic discussion

Stems and roots

The term stem is not used consistently in linguistics. It has been defined as a form to which affixes (of any type) can be attached. Under a different and apparently more common view, this is the definition of a root, while a stem consists of the root plus optional derivational affixes, meaning that it is the part of a word to which inflectional affixes are added. INN stems employ the first definition, while under the more common alternative they would be described as roots.

Translingual communication

Pharmacology and pharmacotherapy (like health care generally) are universally relevant around the world, making translingual communication about them an important goal. An interlingual perspective is thus useful in drug nomenclature. The WHO issues INNs in English, Latin, French, Russian, Spanish, Arabic, and Chinese. A drug's INN names are often cognate across most or all of the languages, but they also allow small inflectional, diacritic, and transliterational differences that are usually transparent and trivial for nonspeakers (as is true of most international scientific vocabulary). For example, although "paracetamolum" (la) has an inflectional difference from "paracetamol" (en), and although "paracétamol" (fr) has a diacritic difference, the differences are trivial; users can easily recognize the "same word". And although "парацетамол" (ru) and "paracetamol" (en) have a transliterational difference, they sound similar, and for Russian speakers who can recognize Latin script or English speakers who can recognize Cyrillic script, they look similar; users can recognize the "same word". Thus INNs make medicines bought anywhere in the world as easily identifiable as possible to people who do not speak that language. Notably, the "same word" principle allows health professionals and patients who do not speak the same language to communicate to some degree and to avoid potentially life-threatening confusions from drug interactions.

Spelling regularization

A number of spelling changes are made to British Approved Names and other older nonproprietary names with an eye toward interlingual standardization of pronunciation across major languages. Thus a predictable spelling system, approximating phonemic orthography, is used, as follows:

- ae or oe is replaced by e (e.g. estradiol vs. oestradiol)

- ph is replaced by f (e.g. amfetamine vs. amphetamine)

- th is replaced by t (e.g. metamfetamine vs. methamphetamine)

- y is replaced by i (e.g. aciclovir vs. acyclovir)

- h and k are avoided where possible

Names for radicals and groups (salts, esters, and so on)

Many drugs are supplied as salts, with a cation and an anion. The way the INN system handles these is explained by the WHO at its "Guidance on INN" webpage. "For example, oxacillin and ibufenac are INN and their salts are named oxacillin sodium and ibufenac sodium. The latter are called modified INN (INNM)."

Comparison of naming standards

See also

- Generic drug

References

External links

- "International Nonproprietary Names". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2012-04-02.Â

- "PharmaStemFinder". BioPharmAnalyses. Retrieved 2015-04-19.Â