On July 20, 2005, Canada became the fourth country in the world, and the first country outside Europe, to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide with the enactment of the Civil Marriage Act which provided a gender-neutral marriage definition. Court decisions, starting in 2003, had already legalized same-sex marriage in eight out of ten provinces and one of three territories, whose residents comprised about 90% of Canada's population. Before passage of the Act, more than 3,000 same-sex couples had already married in those areas. Most legal benefits commonly associated with marriage had been extended to cohabiting same-sex couples since 1999.

The Civil Marriage Act was introduced by Prime Minister Paul Martin's Liberal minority government in the Canadian House of Commons on February 1, 2005 as Bill C-38. It was passed by the House of Commons on June 28, 2005, by the Senate on July 19, 2005, and it received Royal Assent the following day. Following the 2006 election, which was won by a Conservative minority government under new Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the House of Commons defeated a motion to reopen the matter by a vote of 175 to 123 on December 7, 2006, effectively reaffirming the legislation. This was the third vote supporting same-sex marriage taken by three Parliaments under three Prime Ministers in three different years, as shown below.

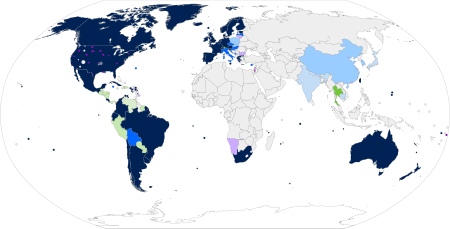

Same-sex marriage by province

Same-sex marriage was legally recognized in the provinces and territories as of the following dates:

- June 10, 2003: Ontario

- July 8, 2003: British Columbia

- March 19, 2004: Quebec

- July 14, 2004: Yukon territory

- September 16, 2004: Manitoba

- September 24, 2004: Nova Scotia

- November 5, 2004: Saskatchewan

- December 21, 2004: Newfoundland and Labrador

- June 23, 2005: New Brunswick

- July 20, 2005 (Civil Marriage Act): Alberta, Prince Edward Island, Nunavut territory, and the Northwest Territories

Note that in some of these cases, the marriage was in fact legal at an earlier date (for example, the Ontario ruling held that marriages performed in January 2001 were legal when performed), but the legality was questioned. As of the given dates, the legality was authoritatively established.

The decision by the Ontario government to recognize the marriage that took place in Toronto, Ontario, on January 14, 2001, retroactively makes Canada the first country in the world to have a government-legitimized same-sex marriage (the Netherlands and Belgium, which legalized same-sex marriage before Canada, had their first in April 2001 and June 2003, respectively).

Overview

Same-sex marriage was originally legalized as a result of court cases in which provincial or territorial justices ruled existing bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional. Thereafter, many same-sex couples obtained marriage licences in those provinces; like opposite-sex couples, they did not need to be residents of any of those provinces to marry there.

The legal status of same-sex marriages in these jurisdictions was unusual. According to the Constitution of Canada, the definition of marriage is the exclusive responsibility of the federal governmentâ€"this interpretation was upheld by a December 9, 2004 opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada (Re Same-Sex Marriage). Until July 20, 2005, the federal government had not yet passed a law redefining marriage to conform to recent provincial court decisions. Until the passage of Bill C-38, the previous definition of marriage was binding in the four jurisdictions where courts had not yet ruled it unconstitutional, but void in the nine jurisdictions where it had been successfully challenged.

Given the Supreme Court ruling, the role of precedent in Canadian law, and the overall legal climate, it was very likely that any challenges to legalize same-sex marriage in the remaining four jurisdictions would be successful as well. Indeed, federal lawyers had ceased to contest such cases and only Alberta's Conservative provincial government remained officially opposed. Alberta Premier Ralph Klein threatened to invoke the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which many law experts argued would not work.

On June 17, 2003, Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chretien announced that the Government would present the bill, which would allow same-sex couples equal rights to marry. A draft of what would become Bill C-38 was released on July 17, 2003, by the Liberal Minister of Justice, Martin Cauchon. Before introducing it into Parliament, the federal Cabinet submitted the bill as a reference to the Supreme Court (Re Same-Sex Marriage), asking the court to rule on whether limiting marriage to heterosexual couples was consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and if same-sex civil unions are an acceptable alternative.

On December 9, 2004, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the marriage of same-sex couples is constitutional, that the federal government has the sole authority to amend the definition of marriage, and the Charter's protection of freedom of religion grants religious institutions the right to refuse to perform the marriage ceremonies for same-sex couples.

Following the Supreme Court's decision, Liberal Justice Minister Irwin Cotler, introduced Bill C-38 on February 1, 2005, to legalize marriage between persons of the same sex across Canada. The Paul Martin government supported the bill but allowed a free vote by its backbench MPs in the House of Commons. Defeat of the bill in Parliament would have continued the status quo and probably incremental legalization, jurisdiction by jurisdiction, via court challenges. This trend could have been reversed only through Parliament passing a new law that explicitly restricted marriage to opposite sex couples notwithstanding the protection of equality rights afforded by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms or by amending the Canadian constitution by inserting the clause "marriage is defined as being between a man and a woman", as was recommended by several conservative religious groups and politicians. Given the composition of the House of Commons at the time, such a measure would have been very unlikely to pass. Conservative Alberta Premier Ralph Klein proposed putting the question to the public at large via a national referendum, but his suggestion was rejected by all four party leaders.

History

Court rulings

Background

- EGALE: A chronological listing of court documents

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in M. v. H. [1999] 2 S.C.R. 3 that same-sex couples in Canada were entitled to receive many of the financial and legal benefits commonly associated with marriage. However this decision stopped short of giving them the right to full legal marriage. Most laws which affect couples are within provincial rather than federal jurisdiction. As a result, rights varied somewhat from province to province.

On January 14, 2001, Rev. Brent Hawkes forced the issue by performing two same-sex marriages, taking advantage of the fact that Ontario law authorizes him to perform marriages without a previous license, via the issuance of banns of marriage. The registrar refused to accept the records of marriage, and a lawsuit was commenced over whether the marriages were legally performed. In other provinces, lawsuits were launched seeking permission to marry.

In 2002 and 2003, court decisions in the superior courts of Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia held that the restriction of marriage to opposite-sex couples was discriminatory and contrary to the equality clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights of Freedoms.

- in Ontario, a trial court decision: Halpern v. Canada (Attorney General) 95 C.R.R. (2d) 1 (Ontario Superior Court, July 12, 2002)

- Text of ruling

- in Quebec: Hendricks v. Quebec [2002] R.J.Q. 2506 (Quebec Superior Court, September 6, 2002)

- Text of ruling (in French)

- in British Columbia: Barbeau v. British Columbia 2003 BCCA 251 (Court of Appeal for BC, May 1, 2003)

- Text of the ruling

The courts in each case suspended the effect of the declarations of invalidity for two years, to allow the federal government to consider legislative responses to the rulings. However, on June 10, 2003, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled on an appeal in the Halpern case. The Court agreed with the lower court that the traditional definition of marriage was discriminatory and that same-sex marriage was legally permitted. However, unlike the previous three court decisions, the Court of Appeal did not suspend its decision to allow Parliament to consider the issue. Instead, it ruled that the 2001 marriages were legal and same-sex marriage was available throughout Ontario immediately: Halpern v. Canada (Attorney General)., [2003] O.J. No. 2268, 2003 CanLII 26403 (Ont. C.A.).

The federal Liberal government had appealed the trial decisions to the provincial courts of appeal, but following the decision on the Ontario Court of Appeal, Prime Minister Chrétien announced on June 17, 2003 that the federal government would not seek to appeal the decisions to the Supreme Court. Instead, the Government would propose a draft Civil Marriage Act and refer it to the Supreme Court for an advisory opinion.

Ontario decision

In 2003, the couples in Halpern v. Canada appealed the decision, requesting that the decision take effect immediately instead of after a delay. On June 10, 2003, the Court of Appeal for Ontario confirmed that current Canadian law on marriage violated the equality provisions in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in being restricted to heterosexual couples. The court did not allow the province any grace time to bring its laws in line with the ruling, making Ontario the first jurisdiction in North America to recognize same-sex marriage. The first same-sex couple married after the decision were Michael Leshner and Michael Stark. Consequently, the City of Toronto announced that the city clerk would begin issuing marriage licences to same-sex couples. The next day, the Ontario attorney general announced that his government would comply with the ruling.

The court also ruled that two couples who had previously had a wedding ceremony in the Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto using an ancient common-law procedure called the reading of the banns would be considered legally married.

On September 13, 2004, the Ontario Court of Appeal declared the Divorce Act also unconstitutional for excluding same-sex marriages. It ordered same-sex marriages read into that act, permitting the plaintiffs, a lesbian couple, to divorce.

British Columbia decision

A ruling, quite similar to the Ontario ruling, was issued by the B.C. Court of Appeal on July 8, 2003. Another decision in B.C. in May of that year had required the federal government to change the law to permit same-sex marriages (see above). The July ruling stated that "any further delay... will result in an unequal application of the law between Ontario and British Columbia". A few hours after the announcement, Antony Porcino and Tom Graff became the first two men to be legally wed in British Columbia.

Quebec decision

On March 19, 2004, the Quebec Court of Appeals ruled similarly to the Ontario and B.C. courts, upholding Hendricks and Leboeuf v. Quebec and ordering that it take effect immediately. The couple who brought the suit, Michael Hendricks and René Leboeuf, immediately sought a marriage licence; the usual 20-day waiting period was waived, and they were wed on April 1 at the Palais de justice de Montréal.

Given the populations of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec, more than two-thirds of Canada's population lived in provinces where same-sex marriage had been legalized after the Quebec decision.

Yukon decision

On July 14, 2004, in Dunbar & Edge v. Yukon (Government of) & Canada (A.G.), 2004 YKSC 54, the Yukon Territorial Supreme Court issued another similar ruling with immediate effect. Rather than reproducing the Charter equality arguments used by the other courts, the Court ruled that since the provincial courts of appeal had ruled that the heterosexual definition of marriage was unconstitutional, it was unconstitutional across Canada. The position was strengthened by the Attorney General's refusal to appeal those rulings. It further ruled that to continue to restrict marriages in Yukon to opposite-sex couples would result in an unacceptable state of a provision's being in force in one jurisdiction and not another.

On August 16, 2004, federal justice minister Irwin Cotler indicated that the federal government would no longer resist court cases to implement same-sex marriage in the provinces or territories.

Manitoba decision

On September 16, 2004, Justice Douglas Yard of the Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench declared the then-current definition of marriage unconstitutional. The judge said that his decision had been influenced by the previous decisions in B.C., Ontario, and Quebec. This decision followed suits brought by three couples in Manitoba requesting that they be issued marriage licences. Both the provincial and federal governments had made it known that they would not oppose the court bid. One of the couples, Chris Vogel and Richard North, had legally sought marriage in a high-profile case in 1974 but had been denied.

Nova Scotia decision

In August 2004, three couples in Nova Scotia brought suit in Boutilier v. Canada (A.G) and Nova Scotia (A.G) against the provincial government requesting that it issue same-sex marriage licences. On September 24, 2004, Justice Heather Robertson of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court ruled the then-current law unconstitutional. Neither the federal nor the provincial governments opposed the ruling.

Saskatchewan decision

Five couples brought suit in Saskatchewan for the recognition of their marriage in a case that was heard by the Saskatchewan Court of Queen's Bench in chambers on November 3, 2004. On November 5, 2004, the judge ruled that excluding same-sex couples from marriage violated the Charter's right to equality and that the common-law definition was discriminatory, thereby bringing same-sex marriage to Saskatchewan.

Newfoundland and Labrador decision

Two lesbian couples brought suit on November 4, 2004 to have Newfoundland and Labrador recognize same-sex marriage. As with the previous decisions, the provincial government did not oppose the suit; moreover, the federal government actually supported it. The case went to trial on December 20 and the next day, Mr. Justice Derek Green ordered the provincial government to begin issuing marriage licences to same-sex couples, an order with which the provincial government announced it would comply.

New Brunswick decision

Two same-sex couples brought suit in April 2005 to request an order requiring the government of New Brunswick to issue same-sex marriage licences. This was granted in June 2005.

The Progressive Conservative premier of New Brunswick, Bernard Lord, who personally opposed same-sex marriage, pledged to follow a directive to provide for same-sex marriages from the courts or from Parliament.

Proceedings in the Northwest Territories

On May 20, 2005, a gay male couple with a daughter brought suit in the Northwest Territories for the right to marry. The territorial justice minister, Charles Dent, had previously said that the government would not contest such a lawsuit. The case was to be heard on May 27 but ended when the federal government legalized same-sex marriage.

Discussion in Parliament, 1995â€"2003

The shift in Canadian attitudes towards acceptance of same-sex marriage and recent court rulings caused the Parliament of Canada to reverse its position on the issue.

On 18 September 1995, the House of Commons voted 124-52 to reject a motion introduced by openly gay Réal Ménard calling for legal recognition of same-sex relationships.

One recent study by Mark W. Lehman suggests that between 1997 and 2004, Canadian public opinion on legalizing same-sex marriage underwent a dramatic shift: moving from minority-support to majority support and that this support was the result of a significant shift in positive feelings towards gays and lesbians.

The first bill to legalize same-sex marriage was a private member's bill tabled in the House of Commons by New Democratic MP Svend Robinson on March 25, 1998. Like most private members' bills it did not progress past first reading, and was reintroduced in several subsequent Parliaments.

In 1999, the House of Commons overwhelmingly passed a resolution to re-affirm the definition of marriage as "the union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others". The following year this definition of marriage was included in the revised Bill C-23, the Modernization of Benefits and Obligations Act 2000, which continued to bar same-sex couples from full marriage rights. In early 2003, the issue once again resurfaced, and the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights proceeded to undertake a formal study of same-sex marriage, including a cross-country series of public hearings. Just after the Ontario court decision, it voted to recommend that the federal government not appeal the ruling. *Proceedings of the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights during the same-sex unions hearings]

Civil status is of provincial jurisdiction in Canada. However, the definition of marriage is a federal law. On June 17, 2003, then Prime Minister Chrétien announced that the government would not appeal the Ontario ruling, and that his government would introduce legislation to recognize same-sex marriage but protect the rights of churches to decide which marriages they would solemnize.

A draft of the bill was issued on July 17. It read:

- 1. Marriage, for civil purposes, is the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others.

- 2. Nothing in this Act affects the freedom of officials of religious groups to refuse to perform marriages that are not in accordance with their religious beliefs.

The draft bill was subsequently referred to the Supreme Court; see below.

On September 16, 2003, a motion was brought to Parliament by the Canadian Alliance (now the Conservative Party) to once again reaffirm the heterosexual definition of marriage. The same language that had been passed in 1999 was brought to a free vote, with members asked to vote for or against the 1999 definition of marriage as "the union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others." Motions are not legislatively binding in Canada, and are mostly done for symbolic purposes. The September vote was extremely divisive, however. Prime Minister Chrétien reversed his previous stance and voted against the motion, as did Paul Martin (who later became Prime Minister) and many other prominent Liberals. Several Liberals retained their original stance, however, and thus the vote was not defined purely along party lines. Controversially, over 30 members of the House did not attend the vote, the majority of whom were Liberals who had voted against legalizing same-sex marriage in 1999. In the end, the motion was narrowly rejected by a vote of 137-132.

Supreme Court Reference re Same-Sex Marriage

In 2003, the Liberal government referred a draft bill on same-sex marriage to the Supreme Court of Canada, essentially asking it to review the bill's constitutionality before it was introduced. The reference as originally posed by Prime Minister Chrétien asked three questions:

- 1. Is the annexed Proposal for an Act respecting certain aspects of legal capacity for marriage for civil purposes within the exclusive legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada? If not, in what particular or particulars, and to what extent?

- 2. If the answer to question 1 is yes, is section 1 of the proposal, which extends capacity to marry to persons of the same sex, consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms? If not, in what particular or particulars, and to what extent?

- 3. Does the freedom of religion guaranteed by paragraph 2(a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protect religious officials from being compelled to perform a marriage between two persons of the same sex that is contrary to their religious beliefs?

Prime Minister Paul Martin later added a fourth in January 2004:

- 4. Is the opposite-sex requirement for marriage for civil purposes, as established by the common law and set out for Quebec in s. 5 of the Federal Law-Civil Law Harmonization Act, No. 1, consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms? If not, in what particular or particulars and to what extent?

The addition of a fourth question considerably delayed the opening of the court reference until well after the June 2004 general election, raising accusations of stalling. The consultative process was held in the autumn of 2004.

In its hearings that began in October 2004, the Supreme Court of Canada accused the government of using the court for other goals when the Government declined to appeal rulings that altered the definition of marriage in several provinces.

"Justice Ian Binnie said it 'may not fulfil any useful purpose' to examine traditional marriage all over again, 'given the policy decision of the government'".

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the government has the authority to amend the definition of marriage, but did not rule on whether or not such a change is required by the equality provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Court stated that such a ruling is not necessary because the federal government had accepted the rulings of provincial courts to the effect that the change was required. The Court also ruled that given freedom of religion in the Charter of Rights, and wording of provincial human rights codes, it was highly unlikely that religious institutions could be compelled to perform same-sex marriages, though because solemnization of marriage is a matter for provincial governments, the proposed Bill could not actually guarantee such protections.

Debate prior to C-38's introduction

On December 9, 2004, Prime Minister Paul Martin indicated that the federal government would introduce legislation expanding marriage to same-sex couples. The government's decision was announced immediately following the court's answer in the Reference re: Same-Sex Marriage reference question.

The Parliamentary bill caused rifts in the House of Commons, especially among the governing Liberals. Many Liberal MPs indicated that they would oppose the government's position in favour of same-sex marriage at a free vote. The majority of each of the Liberal Party, New Democratic Party, and Bloc Québécois voted in favour of the bill; the majority of the Conservative Party voted against the bill.

In 2000, Alberta had amended its Marriage Act to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The law included a notwithstanding clause in an attempt to protect the amendment from being invalidated under the Charter. However, the amendment was invalid since, under the Canadian constitution, the definition of marriage is a federal right. (See Same-sex marriage in Alberta for further discussion of the issue.)

Complicating matters, Conservative Party leader Stephen Harper indicated that a Tory government would work to restore the prohibition on same-sex marriage if Parliament voted to do so in a free vote.

Following the court decision on December 9, Premier Klein suggested that a national referendum be held on same-sex marriage, a measure Prime Minister Martin rejected.

Legislative progress of the Civil Marriage Act

Bill C-38, the Civil Marriage Act, was introduced to Parliament for its first reading in the House on February 1, 2005. Prime Minister Martin launched the debate on February 16. The bill passed second reading on May 4 and third reading on June 28, with votes of 164-137 and 158-133, respectively. It then moved to the Senate, and received its first reading on June 29. Debate was launched on July 4, and a Liberal closure motion limited debate on the bill to only four hours. Second reading and committing the bill occurred on July 6, with a vote of 43-12. The Senate passed Bill C-38 on third reading by a margin of 47 to 21 on July 19, 2005. It received Royal Assent, at the hand of the Rt. Hon. Beverley McLachlin (in her capacity as the Deputy of the Governor General of Canada), on July 20, 2005.

Same-sex marriage in the 39th Parliament

The Conservative Party, led by Stephen Harper, won a minority government in the federal election on January 23, 2006. Harper had campaigned on the promise of holding a free vote on a motion to re-open the debate on same-sex marriage. The motion would re-open the same-sex marriage debate, but did not prescribe restoring the "traditional" definition of marriage.

A news report from CTV on May 31, 2006, showed that a growing number of Conservatives were wary about re-opening the debate over same-sex marriage. One cabinet minister stated he just wanted the issue "to go away", while others including Chuck Strahl and Bill Casey were undecided, instead of directly opposed. Foreign Affairs Minister Peter MacKay noted that not a single constituent had approached him on the issue, and Tory cabinet minister Loyola Hearn was against re-opening the debate.

By November 2006 the debate had shifted and it was the supporters of same sex marriage that were arguing for a fall vote on the issue and the opponents who were lobbying for a delay.

On December 6, 2006, the government brought in a motion asking if the issue of same-sex marriage debate should be re-opened. This motion was defeated the next day in a vote of 175 (nays) to 123 (yeas). Prime Minister Stephen Harper afterwards told reporters, "I don't see reopening this question in the future".

Recognition of foreign legal unions

In Hincks v. Gallardo 2013 CanLII 129 (7 January 2013), the Ontario Superior Court of Justice decided that same-sex partners who entered into UK civil partnerships are to be treated as married for the purposes of Canadian law.

Statistics on same-sex marriage

From June 2003 (date of the first legal same-sex marriages in Ontario) to October 2006, there were 12,438 same-sex marriages contracted in Canada.

Other same-sex partner benefits in Canada

Other kinds of partnership

As mentioned above, Canadian cohabiting same-sex couples are entitled to many of the same legal and financial benefits as married opposite-sex couples. In 1999, after the court case M. v. H., the Supreme Court of Canada declared that same-sex partners must also be extended the rights and benefits of common-law relationships.

The province of Quebec also offers civil unions to same-sex partners. Nova Scotia's Domestic partnerships offer similar benefits. Legislative changes in 2001â€"2004 extended the benefits of common-law relationships in Manitoba to same-sex couples as well as those of different sex.

In 2003, Alberta passed a law recognizing Adult Interdependent Relationships. These relationships provide specific financial benefits to interdependent adults, including blood relations.

Recognition in other provinces and territories

The legal status of same-sex marriages in provinces and territories that did not perform them was uncertain prior to the passage of the Civil Marriage Act. One of the couples that brought suit in Nova Scotia acted so that their Ontario marriage would be recognized.

The Premier of Alberta, Ralph Klein, wanted to prevent same-sex marriages from being performed or recognized in Alberta, but eventually admitted that the province's chances of doing so were slim to none, and said Alberta would obey the legislation. By contrast, the other remaining province without same-sex marriage, Prince Edward Island, announced that it would voluntarily bring its laws into compliance with the federal legislation.

Immigration

The Department of Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) acknowledges same-sex marriages contracted in Canada between immigration applicants and Canadian citizens or permanent residents. Canadians may also sponsor their same-sex common-law or civil union partners for family-class immigration, provided they meet various requirements, including proof of legitimacy, and co-habitation for at least one year.

After the enactment of the Civil Marriage Act, CIC adopted an interim immigration policy which did not recognize same-sex marriages which took place outside Canada. For example, a Canadian citizen, legally married in the Netherlands to his or her same-sex Dutch partner, might not sponsor his or her Dutch partner for immigration as a spouse, despite the fact that both Dutch law and Canadian law made no distinction between opposite-sex and same-sex civil marriages, and despite the fact that CIC did recognize a Dutch opposite-sex marriage.

On December 12, 2006, New Democratic Party MP Bill Siksay introduced a motion in the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration calling on the CIC to immediately rescind the interim policy and "recognize legal marriages of gay and lesbian couples performed in jurisdictions outside Canada for purposes of immigration in exactly the same way as the legal marriages of heterosexual couples are recognized"; the committee voted to recommend that the government do this. In late January 2007, Citizenship and Immigration Minister Diane Finley informed the committee that this would be done. In February 2007, the CIC website was updated to reflect the fact that the policy has been updated.

Military

Since September 2003, military chaplains have been allowed to bless same-sex unions and to perform these ceremonies on a military base.

Survivor benefits

On December 19, 2003, an Ontario court ruled that survivor benefits for Canadians whose same-sex partners died should be retroactive to April 1985, the date the Charter of Rights came into effect. The federal government appealed. On March 1, 2007, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the federal government must pay Canada Pension Plan benefits to surviving same-sex spouses. Initial news reports indicated that the court limited retroactive benefits to only 12 months' worth, but in fact, some survivors may be entitled to benefits dating back to 2000.

Same-sex divorce in Canada

On September 13, 2004, a lesbian couple known as "M.M." and "J.H." in Ontario were granted Canada's first same-sex divorce. Their initial divorce application had been denied based on the fact that the federal Divorce Act defines spouse as "either of a man or a woman who are married to each other". However, Madam Justice Ruth Mesbur of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice ruled that the definition of "spouse" in the Divorce Act was unconstitutional.

In June 2005, a lesbian couple residing in British Columbia obtained a similar ruling.

The Civil Marriage Act in 2005 amended the Divorce Act to permit same-sex divorce. However, prior to 2013, a married couple (gay or straight) could file for divorce in Canada only if at least one spouse was then residing in Canada and had been for at least one full year when the divorce was filed.

In 2012, after the Attorney General of Canada suggested in a divorce case brought in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice that non-residents of Canada did not have valid marriages if such marriages were not recognized by their home jurisdictions, the Conservative government announced that they would fix this "legislative gap". A Government bill, the Civil Marriage of Non-residents Act, positively declaring such marriages legal in Canada and allowing non-residents to divorce in a Canadian court if prohibited from doing so in their home jurisdictions, was introduced and received first reading on February 17, 2012, and passed third and final reading on June 18, 2013. The bill then received a quick passage through the Senate and passed third and final reading on June 21, receiving Royal Assent on June 26. The law came into effect on August 14 by Order of the Governor General in Council made the previous day.

Church and State

Based on the 2001 census, 80% of the Canadian population have been initiated into one of the three main Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Islam, and Christianity). All three have texts that have sections interpreted by some to declare sexual relations between people of the same sex as forbidden and sinful. For example, the Qur'an (7:80-81, 26:165) and the Bible (Leviticus 18:22, Romans 1:26-27, I Timothy 1:9-10, etc.) are frequently interpreted to explicitly forbid homosexuality. (see related article, Homosexuality and religion).

In July 2003, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Canada protested the Chrétien government's plans to include same-sex couples in civil marriage. This is significant because Catholicism has a larger number of adherents in Canada than any other religion or denomination, with 43.6% of the population identifying themselves as Catholic. The church criticisms were accompanied by Vatican claims that Catholic politicians should vote according to their personal beliefs rather than the policy of the government.

Amid a subsequent backlash in opinion, the Church remained remarkably quiet on the subject, at least in public, until late 2004, when two Catholic bishops clearly stated their opposition to same-sex marriage. The Bishop of Calgary, Frederick Henry, in a pastoral letter urged Catholics to fight against the legalization of same-sex marriage, calling homosexual behaviour "an evil act". Bishop Henry's letter also seemed to urge the outlawing of homosexual acts, saying "Since homosexuality, adultery, prostitution and pornography undermine the foundations of the family, the basis of society, then the State must use its coercive power to proscribe or curtail them in the interests of the common good." Two human rights complaints were filed against Henry soon afterward under the Alberta Human Rights act, one of which was dropped at the conciliation stage.

Some major religious groups spoke in favour of legalizing same-sex marriage. The largest Protestant denomination in the country, the United Church of Canada, offers church weddings to same-sex couples and supports same-sex marriages, testifying to this effect during the cross-country Justice Committee hearings. Unitarian Universalist congregations also solemnize same-sex marriages, as do the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and the Metropolitan Community Church. Some progressive Jewish congregations and some within the Anglican Church have also supported same-sex marriage.

The Hutterite Brethren spoke out against same-sex marriage in a letter written to Prime Minister Martin in February 2005. The group has historically not involved themselves with politics.

The Humanist Association of Canada, which endorses a non-theistic, non-religious ethical philosophy to life and full separation of church and state, has been supportive of same-sex marriage. Local affiliate groups of the Humanist Association offer officiancy (marriage commissioner) services across Canada.

Representatives of the World Sikh Organization testified before the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs in favour of the Civil Marriage Act.

Public opinion

In 2012, a poll by Forum Research showed that 66.4% of Canadians approved of legalized same-sex marriage, while 33.6% were opposed. Support for same-sex marriage was highest in Quebec (72%) and British Columbia (70.2%), while lowest in Alberta (45.6%).

A May 2013 Ipsos poll of residents of 16 countries found that 63% of respondents in Canada were in favour of same-sex marriage and another 13% supported other form of recognition for same-sex couples.

See also

- LGBT rights in Canada

- Marriage in Canada

- Members of the 38th Canadian Parliament and same-sex marriage

- Members of the 39th Canadian Parliament and same-sex marriage

- Religion in Canada

- Timeline of LGBT history

- 2005 in LGBT rights

References

Bibliography

- Hull, Kathleen (2006), Same-sex marriage: the cultural politics of love and law, Cambridge Univ. Press, ISBNÂ 0521672511Â

- Lahey, Kathleen A; Kevin Alderson (2004), Same-sex marriage: the personal and the political, Insomniac Press, ISBNÂ 1-894663-63-2Â

- Larocque, Sylvain (2006). Gay Marriage: The Story of a Canadian Social Revolution. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company. ISBNÂ 1-55028-927-6.Â

External links

- Egale Canada Inc.

- Canadians for Equal Marriage

- Same-Sex Marriage Canada

- Marriage Vote Canada

- Defend Marriage Canada

- Redefining Marriage? A Case for Caution Brief to the Parliamentary Justice Committee

- CBC News Indepth: Same-Sex Marriage in Canada

- Full text of NFO CF Group survey (PDF)

- CTV news item

- Supreme Court OK's same-sex marriage

- Institute of Marriage and Family Canada